Making Connections to Overcome Challenges in Engaging the Public in Astronomy

Laura Peticolas Sonoma State University

How do we engage the public in astronomy when the dark skies are disappearing, filled more and more by satellite trails? How do we engage the public in astronomy when cultural values of some members of the public are at odds with astrophysics practices like approaches to knowing? How do we engage the public in astronomy in an environment suspicious of science? How do we engage the public in astronomy when our children's screens are filled with video games, social media, and messages from friends, with no room for education? One may be correct to say that it’s never been more difficult to get our communities out to see the dark sky, the Milky Way, and to successfully share our passion for the universe. But with great challenges come great rewards. Challenges like these can force us outside our comfort zone and into new areas of growth, awareness, and more effective actions, as well as lead us to build new or deeper connections with the people around us. Further, we may learn what works from research, modify our own habits, and hand over the spotlight to join others in activities that are already working.

There are probably as many ways to engage the public in astronomy as there are people on Earth. Here, I propose the simplest, yet perhaps most difficult, way to overcome these challenges: to connect with someone who already successfully works with or educates the communities you wish to reach. While this methodology is now, thankfully, more commonly understood and embraced in science education and outreach fields (e.g., Pompea & Russo, 2021 and Storksdieck et al., 2016), it remains a difficult idea for many astronomers and astrophysicists to implement effectively. This approach may get delegated to an education lead to initiate, or simply ignored for easier science engagement priorities. I firmly believe that if we push ourselves to build professional relationships across cultures, fences, and ideologies, our world could be a better place for all of us.

In the guidance, “Connect with someone who successfully works with or educates the communities you wish to reach,” “connect” may take on a different meaning. I will provide examples of different meanings of “to connect,” but for our purposes, connect means to develop a friendship, build trust, and collaborate with integrity (Maryboy, Begay, & Peticolas, 2012). To begin to connect means to first decide to step out of your comfort zone — that area of expertise where you know more than most — and accept or acknowledge that you lack experience connecting with the community with which you would like to engage. When I say that you have little idea how to connect, I am addressing these moments when you are ready to step outside of your comfort zone. What happens next can unfold in many different ways.

One effective and dependable way to start this journey of connection is to do some research to find out who is working with the community you wish to engage and contact them. When Dr. Lynn Cominsky, the Director of our EdEon STEM Learning group at Sonoma State University, and I were working on an idea to engage autistic teens in NASA science research and topics we did what we know how to do well — speak with those already working with autistic teens. Dr. Cominsky called up the Anova Public School in our county and asked to talk about a proposal on which we were working. As we met with the principal of the school and talked with others, it became clear that we also needed people who specialized in this field. I did a quick search on the National Science Foundation’s Advancing Informal STEM Learning Award Search for autism/autistic, science, and STEM grants that had been funded. Only two grants had been funded and the people working in the area had some of the same team members. We reached out to the Education Development Center team members listed on the grants to see if they were interested in our initial ideas. To our pleasant surprise, they were very interested and helped craft a compelling, authentic, and ultimately successful proposal: NASA’s Neurodiversity Network.

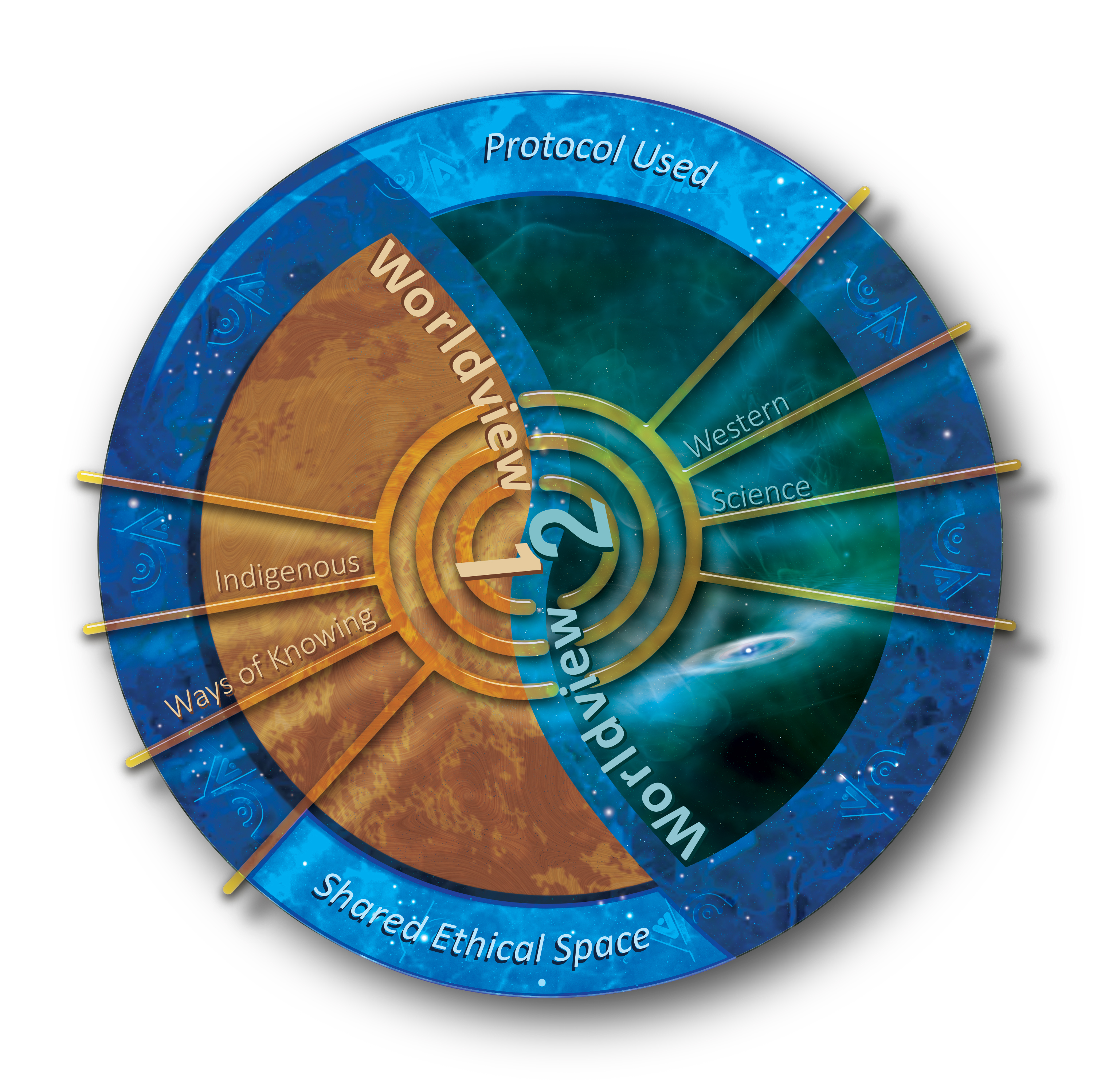

Other times the idea behind the method may be simple, but the process is more difficult or complicated. In these moments, persistence and resilience are your friends. I will share my personal experience here. Drs. Nancy Maryboy, David Begay, Isabel Hawkins, and I were funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to create professional development opportunities to allow informal educators to build relationships and explore commonalities between Indigenous ways of knowing and Western science.1 Our team’s goal was to have 50 percent of our participants identifying as Indigenous (e.g., Native American, Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander) and 50 percent non-Indigenous, all working in fields related to education in informal environments. We already had a wide network of such professionals, but the goal was 45 participants in three regions: Northwest, Hawai‘i-California, and Southwest. We had leveraged our networks to recruit a bit over half of the participant goal. Then, Dr. Begay said, “Let’s start making cold calls.” We did just that. It took courage, many unreturned phone calls, some returned calls and discussions without an application to participate, but ultimately, we had enough people who called us back or asked to meet with us that we filled up our first week-long workshops in each region. After we had this first cadre of participants in each region, finding new participants for the follow-up workshops was relatively easy. (Unfortunately, ~30% dropped out of the program after the first week.) Over the years, many of these participants have become our friends, both on Facebook and in person!

The Eclipse Megamovie crowdsourcing team implemented similar protocols when initiating week-long road tours along the path of totality prior to the total solar eclipse of 2017. Our team was based out of California, primarily at the University of California, Berkeley, Google, and the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. We were recruiting participants to take photographs of the solar chromosphere and corona during totality. We wanted to make sure that local communities under the path of totality were aware of the 2017 eclipse and what to expect, as well as to recruit photographers (Hudson et al., 2021; Peticolas et al., 2020; White et al., 2020). We were in rural America but came from a well-known American urban mecca. We were in politically conservative areas but came from a bastion of liberal thought. Our cultures could not be more different, and a social media propaganda initiative at the time was spreading like wildfire through conservative America about UC Berkeley and its so-called “anti-free speech” and “violent protests,” neither of which were true. Regardless, through cold-calls and professional relationships, we were able to book venues and fill them with interested community members. From there, education, recruitment, support, and crumbling cross-political barriers became more and more possible. Naturally, there were moments when community members wanted to know why UC Berkeley had gone “bad.” There were challenging discussions amongst our diverse photo volunteers. But overall, we recruited over 1,000 volunteers across the political spectrum to unite under a common goal of experiencing and photographing a total solar eclipse. We were thanked for our patience in explaining the reality of what it was like at UC Berkeley. One family said we had changed their adult son's life and moved him from identifying singly as a mechanic to pluralistically as an amateur astronomer and mechanic.

You may realize by now that I haven’t spoken of the importance of setting engagement goals or describe what successful astronomical public engagement looks like. I bring this up because goals are an important and effective way to think about many educational activities. However, when it comes to engaging the public in ways to overcome the challenges mentioned above, I believe we have yet to fully understand what success looks like. Our communities here in America and in many places across the globe are simply too diverse to imagine something without including those communities. In fact, I think prescribing solutions would be a detriment to the challenge at hand. In part, the challenges we face today are built on people having goals without considering that there are other communities that might have something to contribute to those goals. The following is a perhaps controversial example to make my point.

I was honored to be a synthesizer at Ms. Kimura and Dr. Maryboy’s NSF-funded I-WISE conference: Indigenous Worldviews in Informal Science Education — Integration, Synthesis, and Opportunity (Maryboy et al., 2021; Venkatesan & Burgasser, 2017). Together with three others, I supported brainstorming and discussion about the notion of cross-cultural collaboration in astronomy, space science, Earth science, environmental science, and STEM education. In this first conference, we learned from each other about the challenges and benefits of collaborating across cultures. Specifically, our conversations turned to Mauna Kea. Over 30 of us met each day, including the late Native Hawaiian astrophysicist Dr. Paul Coleman, ‘Imiloa Executive Director Ka’iu Kimura, and Dr. Merle Lefkoff, a researcher applying nonlinear complex systems thinking to whole system change often in systems working towards peace and reconciliation. In these deep, and sometimes emotionally painful, conversations, we had an important realization. To do astrophysical research on top of sacred mountains and in space in a non-colonizing way requires astrophysicists and local Indigenous communities to build a common vision without coming to the other with a proposed goal in mind (Venkatesan et al., 2019). This approach has a high likelihood of sustaining peaceful and abundant new discoveries. With this goal in mind, I challenge you to include members of your local community or someone who works with them on a daily basis when brainstorming your next astrophysics or astronomy education proposal ideas. What unimagined ideas may spring forth, to engage young minds, build trust with your community, and bring about newly framed discoveries?

Even if these large-scale cross-cultural projects seem daunting, simply reaching out to your local museum or science center and giving a public talk will offer a bigger bang for your buck. I give public science talks numerous times each year covering the research I did in the past on the aurora on Earth and Mars, on a current NASA research center (NASA’s MACH Center), on building CubeSats with undergraduates and graduate students with multiple diverse universities (Peticolas et al., 2021), and on developing with Dr. Cominsky a 9th-grade science, computer science, technology, engineering, and mathematics curriculum (Learning by Making). These talks, in partnership with a local organization, will expand your “circle of relations,” as Dr. Maryboy calls them.

Any small step toward bridging the gaps that are driving us apart will not only allow you to share your life’s work, but will also move us towards healthy, robust, diverse, and sustainable American learning communities that continue to inspire joy, understanding, and knowledge. I hope you will join me on this boundary-crossing journey. What will your new collaboration with integrity manifest from your planting of seeds? I hope you will share the results with me when they bloom.

1 I use “ways of knowing” based on the research by Maryboy & Begay, 1999 and Barnhardt & Oscar Kawagley, 2005. I use Western science to remind the reader that our astrophysics practices originated culturally from the West, i.e., in Europe.

Citations

- Aikenhead, G., and Michell, H., 2011. Bridging cultures: Indigenous and scientific ways of knowing nature.

- Barnhardt, R., and Oscar Kawagley, A., 2005. Indigenous knowledge systems and Alaska Native ways of knowing. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 36(1), pp.8-23.

- Hudson, H., Peticolas, L., Johnson, C., White, V., Bender, M., Pasachoff, J.M., Oliveros, J.C.M., and Filippenko, A.V., 2021. The Eclipse Megamovie Project (2017). Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 24(4), pp.1080-1089.

- Maryboy, N.C., and Begay, D.H., 1999. Living the Order: Dynamic Cosmic Process of Dine Cosmology. Nanit'a Sa'ah Naaghai Nanit'a Bik'eh Hozhoon (Doctoral dissertation, California Institute of Integral Studies).

- Maryboy, N., Hawkins, I., Peticolas, L., Stein, J., Valdez, S., and Kimura, K., 2021. I-WISE: A Foundational Conference on Indigenous Worldviews in Informal Science Education. The Informal Learning Review, (166).

- Peticolas, L., Hudson, H., Johnson, C., Zevin, D., White, V., Oliveros, J.C.M., Ruderman, I., Koh, J., Konerding, D., Bender, M., Cable, C., Kruse, B., Yan, D., Krista, L., Collier, B., Fraknoi, A., Pasachoff, J., Filippenko, A., Mendez, B., McIntosh, S., and Filippenko, N., 2019. Eclipse megamovie 2017 successes and potential for future work. Celebrating the 2017 Great American Eclipse: Lessons Learned from the Path of Totality, 516, p.337.

- Peticolas, L.M., Jernigan, G., Cominsky, L., Bartolone, L.M., Lugaz, N., Alfred, M., Lessard, M., Kim, C., Smith, S., Mehta, S., Diaz Ramirez, E., Mora, O., Gopar Carreno, C., Foster, W., Blais, S., Dawson, J., Vasquez, A., Castellanos Vasquez, E., Sager, T., Davis, R., Gales, M., Jean-Baptiste, W., Kierstdet, T., Ogunbanjo, O., Whitfield, J., Williams, A., Burgett, J., Chesley, A., Jiang, H., Campbell, J., Bisson, K., Coston, K., Bradley, L., and Davis, H.B., 2021. Engaging Hispanic Students, Latinx Students, and their Peers in the 3U3 CubeSat Project, AGU abstract ED32A-06, Fall Meeting 2021.

- Pompea, S., and Russo, P., 2021. Ten simple rules for scientists getting started in science education. PLOS Computational Biology, 17(12), p.e1009556.

- Storksdieck, M., Stylinski, C., and Bailey, D., 2016. Typology for public engagement with science: a conceptual framework for public engagement involving scientists. Center for Research on Lifelong STEM Learning.

- Venkatesan, A., Begay, D., Burgasser, A.J., Hawkins, I., Kimura, K.I., Maryboy, N., and Peticolas, L., 2019. Towards inclusive practices with Indigenous knowledge. Nature Astronomy, 3(12), pp.1035-1037.

- Venkatesan, A., and Burgasser, A., 2017. Perspectives on the Indigenous Worldviews in Informal Science Education Conference. The Physics Teacher, 55(8), pp.456-459.

- White, V., Peticolas, L., Johnson, C., Zevin, D., Ruderman, I., Hudson, H., Kruse, B., Mendez, B., Bender, M., & Collier, B. 2018, Proc. of the Communicating Astronomy with the Public.